The Tucker Interview Guide: Part III

The Golem and some Kabbalah

Let’s resume with one of the trickier episodes of the interview: The One Where Tucker Asks What a Golem Is.

00:31:57

Tucker: Tell us what a golem is.

00:31:59

Me: Man, never thought. This would be the part, Tucker’s asking me what a golem is, where the movie would do the record scratch freeze frame. You might be wondering how I got here. Tell us what a golem is, Con.

The Golem: “an artificial man into which a ba’al shem, or Master of the Name, could breathe life by pronouncing one of the secret divine names according to a special formula.”

For special formula you might also say “algorithm.”

The best source for this idea of equating the mythical figure of the Golem with computers is Gershom Scholem, who pioneered the modern, academic study of Kabbalah. A good book by him for this is On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism (1965) and specifically the chapter “The Idea of the Golem.”

For our purposes here, however, we just need his article for Commentary Magazine which summarizes his ideas quite succinctly.

This is the preface for his piece in Commentary. Scholem had suggested the first computer of its kind in Israel should literally be named “Golem.”

When, a year ago, Gershom Scholem, the foremost authority of our day on Jewish mysticism, heard that the Weizmann Institute at Rehovoth in Israel had completed the building of a new computer, he told Dr. Chaim Pekeris, who “fathered” the computer, that, in his opinion, the most appropriate name for it would be Golem, No. 1 (“Golem Aleph”). Dr. Pekeris agreed to call it that but only on condition that Professor Scholem would dedicate the computer and explain why it should be so named. What follows are Professor Scholem’s dedicatory remarks, which were delivered at the Weizmann Institute on June 17, 1965.—Ed.

As you go into Scholem’s article, here is the crucial analogy:

Now, this idea of the Golem is deeply ingrained in the thinking of the Jewish mystics of the Middle Ages known as the Kabbalists. I want to give you at least an inkling of what lies behind the idea. It may be far removed from what the modern electronic engineer and applied mathematician have in mind when they concoct their own species of Golem—and yet, all theological trappings notwithstanding, there is a straight line linking the two developments.

As a matter of fact, the Golem—a creature created by human intelligence and concentration, which is controlled by its creator and performs tasks set by him, but which at the same time may have a dangerous tendency to outgrow that control and develop destructive potentialities—is nothing but a replica of Adam, the first Man himself. God could create Man from a heap of clay and invest him with a spark of His divine life force and intelligence (this, in the last analysis, is the “divine image” in which Man was created). Without this intelligence and the spontaneous creativity of the human mind, Adam would have been nothing but a Golem—as, indeed, he is called in some of the old rabbinic stories interpreting the Biblical account. When there was only the combination and culmination of natural and material forces, and before that all-important divine spark was breathed into him, Adam was nothing but a Golem. Only when a tiny bit of God’s creative power was passed on did he become Man, in the image of God. Is it, then, any wonder that Man should try to do in his own small way what God did in the beginning?

It would probably take a hefty theological book to truly unpack that paragraph. I’ll just say this: that man might attempt to do what God did in Eden and, like God, end up having his own “intelligent creature” rebel against him, would be perfect historical irony. Indeed, if man’s creation ended the world through intelligence rebellion, ala what happened in Genesis, that would even be a case of what my friend Herald Gandi said is, “the end mirroring the beginning” in the Bible.

Scholem has a whole list on the similarities between Kabbalah and computing. The first one:

“This is where we may well ask some questions, comparing the Golem of Prague with that of Rehovoth, the work of Rabbi Jehuda Loew with the work of Professor—or should I say, Rabbi?—Chaim Pekeris.

Have they a basic conception in common? I should say, yes. The old Golem was based on a mystical combination of the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, which are the elements and building-stones of the world. The new Golem is based on a simpler, and at the same time more intricate, system. Instead of 22 elements, it knows only of two, the two numbers 0 and 1, constituting the binary system of representation. Everything can be translated, or transposed, into these two basic signs, and what cannot be so expressed cannot be fed as information to the Golem. I daresay the old Kabbalists would have been glad to learn of this simplification of their own system. This is progress.”

A book by Nathan Abrams on Stanley Kubrick’s influences led me to Scholem on this subject. (Kubrick made one finished and one unfinished movie about A.I.)

“If a practical use of Kabbalah was the creation of golems, namely powerful androids animated by the appropriate incantations consisting of mathematical permutations and combinations of the letters that made up various mystical names of God, then this bears much similarity with modern computer science. The animation of inert, inanimate objects by imputing the correct sequences of letters is precisely the task of computer scientists who are hence, in practical terms, modern Kabbalists. Mitchell P. Marcus writes, “Without the correct programming, our computers are just inanimate, inert objects. By virtue of the correct programs, of the correct sequences of letters and symbols, we animate these machines and make them do our will.” This connection between computer programming and the use of practical Kabbalah to create automata was well recognized when, as he observed in Commentary magazine in 1966, Gershom Scholem named the first computer in Israel “Golem.” The creation of such a golem was, as Scholem notes, “in some sense competing with God’s creation of Adam” and “in such an act the creative power of man enters into a relationship, whether of emulation or antagonism, with the creative power of God.” Clarke confirms this when he writes, “‘God made man in His own image.’ This, after all, is the theme of our movie.”

Abrams, Nathan. Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual (p. 134). Rutgers University Press. Kindle Edition.

The film Clarke refers to being 2001: A Space Odyssey, of course.

“Kubrick also consulted the modern descendants of the kabbalists. He read Marvin Minsky’s 1961 article, “Steps towards Artificial Intelligence,” and arranged to meet him in London in 1965. Minsky was the head of the Artificial Intelligence Project at MIT and advised Kubrick on the subject. (One hears an echo of his name in that of the hibernating Discovery crew member Dr. Kaminsky.) Minksy revealed in the late 1960s, around the time that Kubrick was making 2001, that his grandfather told him that he was a descendant of Rabbi Judah Loew (1525–1609), the Maharal of Prague, the famous Kabbalist who created a golem. Kubrick also met with Irving John “Jack” Good, a statistician and mathematical genius who contributed to cracking the German Enigma codes during World War II, as well as working on the pioneering computer, Colossus. He subsequently published Speculations concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine and Logic of Man and Machine (both 1965). Good’s father, Moshe Oved, was also a Kabbalist. And Scholem described wheelchair-bound Jewish nuclear strategist, John von Neumann, one of the sources for Dr. Strangelove, as Loew’s “spiritual ancestor,” from whom Neumann claimed descent, one of those who has “contributed more than anyone else to the magic that has produced the modern Golem.”18

Abrams, Nathan. Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual (p. 126). Rutgers University Press. Kindle Edition.

And then this from the book about Jack Parsons, which includes a section on his mentor Theodore von Kármán:

“Born in Budapest on May 11, 1881, von Kármán was descended from Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel of Prague, and he often boasted of his ancestor’s reputation for having created a golem, “an artificial human being in Hebrew folklore endowed with life.”2 Unmentioned in his autobiography, The Wind and Beyond, the golem appears in several secondary sources. Though not relevant to our discussion of GALCIT, the creation of the golem is a topic we will return to later when we discuss “magical children.”

Carter, John. Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons (p. 8). Feral House. Kindle Edition.

Of all those men who claim or are said, metaphorically, to be the descendent of Rabbi Loew, von Kármán is seemingly the only one who truly was.

Now with all this alleged Kabbalah influence within the history of computing, and specifically A.I., some people (i.e. people who like to blame the Jews for all their problems) are never far from from wanting to take this in an anti-Jewish direction.

It should be remembered, then, that the Kabbalah is, ironically, also beloved by anti-Semites. The proto-Nazi Ariosophist, Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, was characteristic of many earlier generations of anti-Semites in this:

Finally, Lanz was deeply invested in the power of East and South Asian symbols, which he believed to have the same roots as Ario-Germanic runes in Europe. He favoured Hindu concepts such as reincarnation and karma to Christian ideas of Heaven and Hell, dabbling in the kabbalah (oddly, a common theme among otherwise radical anti-Semites).147

Kurlander, Eric. Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich (pp. 21-22). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

And then there’s the historic contention of the Kabbalah possibly being of Gnostic origin. That it was only adopted by Jewish people at a much later time. This is stated here by the occultist and occult historian John Michael Greer:

“Gershom Scholem, still the best historian of the Cabala (and a Jew), showed in his book The Origins of the Kabbalah that it wasn’t originally Jewish at all, but was borrowed into Judaism from the Gnostic movement in the 11th century AD.

The early Jewish Cabalists took the tradition from the Gnostics and reworked it to fit the needs of their religion. By the 14th century the same tradition had been taken up, partly via Jewish sources, by Christian Cabalists, and that latter movement is what gave rise to the modern occult Cabala. It’s borrowed considerably from the Jewish Cabala from time to time, but its core is Middle Platonism with a strong Pythagorean influence.” - link to the Tweet

My friend Mordechai Shinefield, who recently became a rabbi, had this to say about Greer’s tweet about Scholem and the origins of Kabbalah possibly being of gnostic, and not Jewish, origin:

“There’s a very popular argument that kabbalah purports to be an ancient tradition but is really a medieval gnostic tradition. imo this fails to deal with midrashic, aggadatic and prophetic antecedents that to me very obviously carry proto-kabbalistic themes. stuff like entering Pardes, dealing with demons, seeing the divine chariot, traveling through the celestial spheres — all of these do date back to legitimate ancient texts. so i choose to believe that the zohar/kabbalah is moshe de leon’s take on a real evolving oral (and in some places textual) tradition, and not a forgery or merely a port-over of gnostic ideas.”

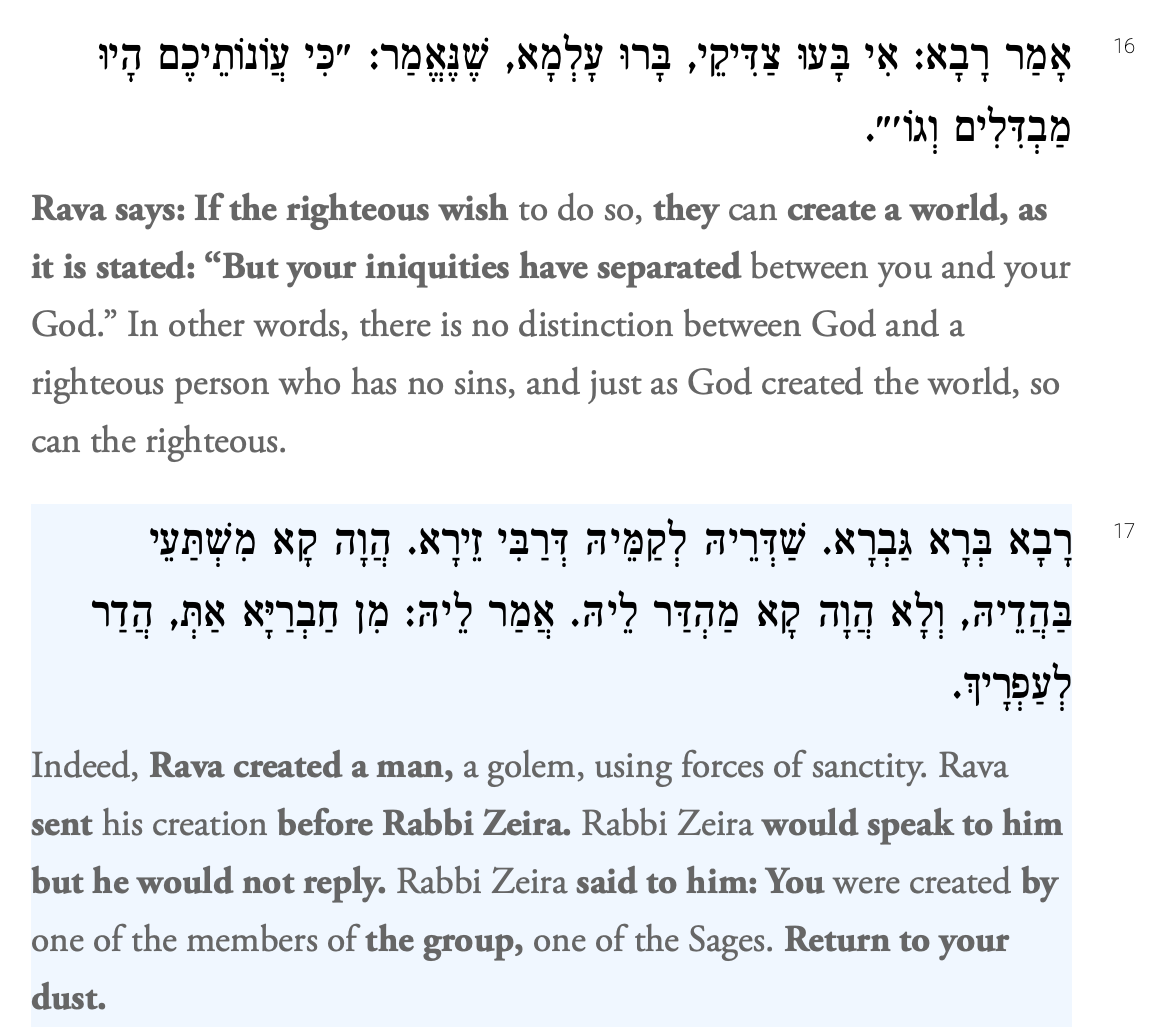

Mordy added that the below is from Sanhedrin 65b (the Talmud). This would locate it in the pre-medieval era, and so “for any theory that says that it comes by way of ancient Babylon it’s still compatible,” but he points out that it does push back against the idea that it merely arose in the medieval era.

It sounds like, as always, more study is needed.

Elsewhere, Gershom Scholem had the ur-gnostic sorcerer Simon Magus (who appears in the book of Acts) as possibly creating a Golem.

“In the semi-gnostic chapters of the ‘homilies’ on Simon Magus we find a striking parallel to the above-mentioned conceptions of the Jewish thaumaturges and to the likewise semi-gnostic ideas of the Book Yetsirah. Simon Magus is quoted as boasting that he had created a man, not out of the earth, but out of the air by theurgic transformations (theiai tropai) and--exactly as later in the instructions concerning the making of the golem!-reduced him to his element by ‘undoing’ the said transformations…

…What here is accomplished by transformations of the air, the Jewish adept does by bringing about magical transformations of the earth through the influx of the ‘alphabet’ of the Book Yetsirah. In both cases such creation has no practical purpose but serves to demonstrate the adept’s ‘rank’ as a creator. It has been supposed that this passage in the Pseudo-Ciementines came, by ways unknown, to the alchemists, and finally led to Paracelsus’ idea of the homunculus.1 The parallel with the Jewish golem is certainly more striking. The ‘divine transformations’ in the operation of Simon Magus remind one very much of the creative ‘transformations’ (temuroth) of letters in the Book Yetsirah.” - On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism, Gershom Scholem

Scholem also came to believe that in the evolution of the Golem story that the creation of one to be a kind of mere servant was a late addition. The question, then, of the Golem’s servile nature was something that had been discussed in an exchange of letters between Hannah Arendt and Scholem.

Arendt:

“Once again to the question of the Golem study: at the beginning, you mention the relationship to Adam, and you distance yourself somewhat from the telluric implications of Adam-adamah. Above all, you say that the “servant” idea in the Golem is quite late. I have a question. It states explicitly in Genesis that Adam was created in order to look after the earth. Here, then, the telluric element already seems connected to “service,” if not, of course, in the sense of the Golem story.7 I’ve always been interested in this passage, for a different reason. People normally think that work is somehow connected to the expulsion from paradise; but it seems to me that work, in the sense of tillage, is implied in the creation story from the very beginning. According to the text, the only difference after the expulsion is that work became arduous and difficult.” - Hannah Arendt, in a letter to Gershom Scholem

That the A.I. revolution might finally free mankind from the Edenic curse of having to work is something I bring up towards the end of the Tucker interview. Eric Hoffer, who also corresponded with Arendt, had this to say about the machines and the upcoming age of automation. He, too, connected it with the Edenic curse of work and its potential reversal:

Eric Hoffer (All quotes from his book The Temper of Our Time):

“The moment man ate from the tree of knowledge God had His worst fears confirmed. He drove man out of Eden and cursed him for good measure. But you do not stop a conspirator from conspiring by exiling him. I can see Adam get up from the dust after he had been bounced out, shake his fist at the closed gates of Eden and the watching angels, and mutter: “I will return.” Though condemned to wrestle with a cursed earth for his bread and fight off thistles and thorns, man resolved in the depths of his soul to become indeed a creator—to create a manmade world that would straddle and tame God’s creation. Thus all through the millennia of man’s existence the vying with God has been a leading motif of his strivings and efforts.

…

I said to myself: “The skirmish with God has now moved all the way back to the gates of Eden. Jehovah and his angels with their flaming swords are holed up in their Eden fortress, and we with our automated machines are hammering at the gates. And right there, in the sight of Jehovah and his angels, we shall declare null and void the ukase that with the sweat of his face man shall eat bread.”

…

The fact is that the mad rush of the last hundred years has left us out of breath. We have had no time to swallow our spittle. We know that the automated machine is here to liberate us and show us the way back to Eden; that it will do for us what no revolution, no doctrine, no prayer, and no promise could do. But we do not know that we have arrived. We stand there panting, caked with sweat and dust, afraid to realize that the seventh day of the second creation is here, and the ultimate sabbath is spread out before us.

Hoffer, Eric. The Temper of Our Time. Hopewell Publications. Kindle Edition.

Back to Eden. The end is the beginning.

At the conclusion of his 1966 article on the Golem for Commentary, Scholem concludes on an ominous note. A reminder of how the original Eden ended.

All my days I have been complaining that the Weizmann Institute has not mobilized the funds to build up the Institute for Experimental Demonology and Magic which I have for so long proposed to establish there. They preferred what they call Applied Mathematics and its sinister possibilities to my more direct magical approach. Little did they know, when they preferred Chaim Pekeris to me, what they were letting themselves in for. So I resign myself and say to the Golem and its creator: develop peacefully and don’t destroy the world. Shalom.

Note: For more precedents of A.I. monsters, read my post on Shelley’s Frankenstein here.

Conrad. Wonderful. I LOOK FORWARD TO MORE on this topic of AI as golem as disgruntled Adam with a cosmic/computer pry-bar at the gates of Eden working by hook (magic) or crook (mathematics) to usurp The Throne. Keep up the Good work. It is so very important. You are the Ironman to the Nick Land(ish) Ultron.